The Inside Story of How a Nazi Plot to Sabotage the U.S. War Effort Was Foiled

J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI took the credit, but it was really only because of a German defector that the plans were blown

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e2/f8/e2f889b0-34db-4c37-b866-140617906988/hell_gate_bridge_nps.jpeg)

The New York Times headline on July 4, 1942, was almost jubilant, an Independence Day gift to a country in the throes of war: “Nazi Saboteurs Face Stern Army Justice.” The article described a plot thwarted and an FBI that was vigilant against threats to public safety. It included a line drawing of J. Edgar Hoover on an important phone call.

The article was also terrifying. Eight agents of Nazi Germany were in custody, caught on American soil with detailed plans to sabotage key infrastructure and spread panic. In late June, two squads of German saboteurs had landed on American beaches, ferried by U-boats to Long Island and Florida’s coast. The saboteurs had enough explosives for two years of mayhem, with immediate plans to blow up a critical railway bridge, disrupt New York’s water supply and spread terror. They were stopped in the nick of time.

The reality was even scarier than the Times reported, and strikingly different from the story presented by the FBI: a defense system caught unawares, plotters who were merely human, and a confession nearly bungled by the agency.

While Hoover and his FBI painted the arrests as a great coup, in fact it was mere chance that brought the Nazi plot to light.

That’s not to say Hoover’s crew wasn’t looking for Nazis. The FBI had been alert to schemes on U.S. soil since the Pearl Harbor attack jolted the nation’s defense system. The agency had even infiltrated a ring of Nazi spies based in New York and arrested them the year before, in 1941. That ring was led by a man named Frederick “Fritz” Duquesne, a South African who had lived in New York for over 30 years. With a shell business in Manhattan and orders from Berlin, Duquesne assembled a network of operatives including one who obtained information about shipping targets and was preparing a fuse bomb. Another plotter designed power plants for utility companies in New York. By the fall of 1940, they were mapping industrial targets in the Northeast. The arrests of Duquesne and his ring in June 1941 had been a publicity windfall for Hoover and a wake-up call for the nation.

The problem was that after Pearl Harbor, the FBI was looking in many wrong directions for saboteurs, including a misguided dragnet effort against immigrant families on both coasts.

This new batch of saboteurs, all long-time U.S. residents, were trained for their mission in Germany at an estate called Quentz Lake outside Berlin. Hitler’s generals had been clamoring for sabotage operations and that pressure worked down to Walter Kappe, an army lieutenant who had lived in Chicago and New York in the 1930s before returning to serve the Reich. Kappe began recruiting in 1941 from among other Germans who had also repatriated from America. Leading the group was the oldest, George Dasch, age 39, a long-time waiter in New York who had served in the U.S. Army. Others included Ernest Berger, who had gone so far as to obtain U.S. citizenship. Kappe’s plan was to send the team ahead to settle in before he arrived in Chicago to direct sabotage operations. They would be paid handsome salaries, be exempt from military service, and receive plum jobs after Germany won the war.

All the agents Kappe selected had lived in the United States for years – two had U.S. citizenship. Their training was rigorous and they practiced their fake identities, rehearsing every detail. There was even a built-in protocol to protect the operation from the temptation to defect, as William Breuer notes in Nazi Spies in America: “If any saboteur gave indications of weakening in resolve… the others were to ‘kill him without compunction.’”

Their operation was dubbed Pastorius, named for the founder of the first German settlement in America (Germantown, later absorbed into Philadelphia). The eight secret agents would sail in two groups from a submarine base in Lorient, France. The first group boarded the night of May 26 and U-201 submerged for the voyage. U-202 followed two nights later, less than six months after the U.S. and Germany declared war on each other.

On the beach of Long Island’s south fork on June 12, the night of the Pastorians’ arrival, was not the FBI but a young Coast Guard recruit named John Cullen, strolling the sands near Amagansett. Cullen was understandably stunned when he spotted four men in German uniforms unloading a raft on the beach. Cullen, 21, was unarmed. Wearing the fatigues was a tactical choice: If the men were captured in them, they would be treated as prisoners of war rather than spies subject to execution.

He rushed toward the group and called out for them to stop. Dasch went for the young man and grabbed his arm, managing to threaten and bribe him at the same time. Dasch shoved a wad of cash into Cullen’s hand, saying in clear English, “Take this and have a good time. Forget what you’ve seen here.” The young man raced off back in the direction of the Coast Guard station, while Dasch and his team quickly buried their uniforms and stash of explosives and detonators to retrieve later. When Cullen returned to the beach at daylight with several Coast Guard officers, they found footprints that led to the cache.

But the Germans had gotten away. At Amagansett they boarded a Long Island Railroad train into the city. Dasch bought four newspapers and four tickets, and the saboteurs blended into the Manhattan-bound commuters on the 6:57 a.m. train. When they reached the city they split into two groups: two agents checked into a hotel across from Penn Station, and the other two headed for a second hotel.

A few days later, on June 17, off the Florida coast just below Jacksonville, U-201 surfaced and deposited the second quartet of saboteurs before dawn. Following procedure, they buried their explosives and uniforms near the beach, walked to nearby Highway 1, and caught a Greyhound for Jacksonville. Within a day, two were bound for operations in Chicago, and the other two headed for Cincinnati. Their list of targets included the complex systems of canal locks in Cincinnati and St. Louis at the heart of commerce on the Mississippi and aluminum factories in Philadelphia.

Operation Pastorius appeared to be on track.

The New York plotters chose their targets for maximum suffering and symbolism. The Hell Gate Bridge carried four vital rail arteries – two for passengers, two for freight – across the most densely populated and economically important passage of the Northeast. The bridge was also an icon of American engineering. Other transportation targets were Newark Penn Station and the “Horseshoe Curve” on the Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad at Altoona, Pennsylvania. Another big target was the New York water supply, a gem of public utilities and health. The state’s Board of Water Supply, aware of the vulnerability, had boosted wartime security for the system to include 250 guards and more than 180 patrolmen.

Once the plotters confirmed logistics, they would retrieve their cache of explosives near Amagansett.

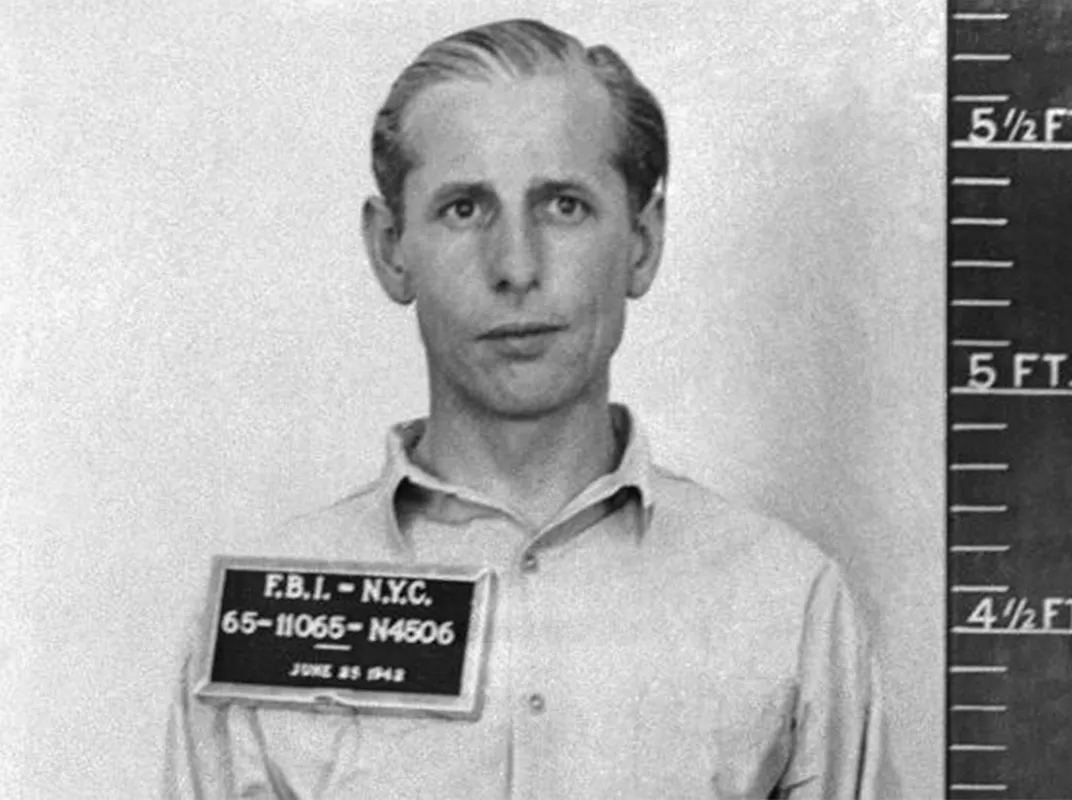

When Dasch checked into the hotel with fellow conspirator Berger, though, he used the moment to tell Berger that he planned to call the FBI and expose their scheme. He told Berger he could either join his planned defection or Dasch would kill him. Then Dasch made a phone call to the local FBI office.

He never wanted to return to Germany; he thought if he turned the operation in, he could stay in America and perhaps resume his life. Dasch had originally stowed away on a freighter headed for the U.S., arriving in 1922. He and his Pennsylvanian wife both pined to stay in the States. If Dasch hadn’t given himself up, would they have been successful? The odds were in their favor.

Dasch told the FBI agent who answered that a Nazi submarine had just landed and he had important information. “I’ll be in Washington within the week to deliver it personally to J. Edgar Hoover,” he said, then hung up.

The FBI had received hundreds of many prank or misguided calls since the war started, and this seemed to be one more. But when the same office got a call from the Coast Guard about the Long Island episode and the stash of explosives retrieved on the beach, the FBI took the anonymous call seriously.

Dasch soon broke free from his team in New York, however, and boarded a train for Washington, D.C. He phoned FBI headquarters when he got there. “I’m the man who called your New York office,” he said. “I am in Room 351 at the Mayflower Hotel.” He asked to speak with Hoover. He was not put through.

For the next two days, dumbfounded FBI agents interrogated Dasch in his hotel room with a stenographer taking down his story: from the sabotage training outside Berlin to the targets identified by both teams, and contacts’ addresses in America. He also handed over all the cash the German government had provided to bankroll years of chaos: over $82,000. Within 14 days, all eight saboteurs were in jail, a string of arrests from New York to Chicago.

None of the infrastructure targets were hit. Public alarm, however, skyrocketed when the news broke. Roosevelt ordered a military tribunal, as the Times headline noted, the first time one had been called since Lincoln’s assassination. All eight defendants pled not guilty, saying they had volunteered for the operation only to get back to their families in America.

Hoover knew the only way to catch up was to manage the spin. He stage-managed the press details of the case, framing the captures as brilliant police work, when in fact Dasch had volunteered the names and addresses. In newsreels produced through the war, Hoover looked into the camera and addressed GIs overseas, assuring them that the FBI was their capable ally in the war to protect America.

Dasch hoped the risks he took to alert authorities to the scheme would get him clemency, but they were lost in accounts of a triumphant FBI. The Washington Post reported only that Dasch “cooperated with United States officials in procuring evidence against the others.”

That July even Hoover reportedly wavered on executing the man who handed the case to him on a platter. In the end, Attorney General Francis Biddle requested leniency for Dasch. The military tribunal found all eight guilty and sentenced them to death. Dasch’s sentence was reduced to 30 years in prison, and Berger’s sentence reduced to life.

On August 8, the six condemned to die were taken to the District of Columbia Jail and executed by electric chair. Prison officials were concerned about the power surge – the chair was relatively untested locally. Each execution took 14 minutes. News cameras filmed the ambulances bearing the bodies away afterward.

(UPDATE, June 26, 2017: The Washington Post recently reported that in 2006, the National Park Service uncovered a clandestine memorial to the six Nazi spies.)

After serving six years of their sentence, Dasch and Berger were released. Dasch’s lawyer repeatedly applied for his client’s amnesty, and by 1948 President Truman leaned toward a pardon. Still, Hoover argued against it. Dasch accepted deportation as a condition of pardon, and both prisoners were released and sent to what was then West Germany, where they were treated as pariahs. Dasch settled with his wife in a small town and started a small business, only to have news coverage expose him. They had to flee crowds threatening vigilante justice to the “traitor” and start over in another town. A friend told him, “It’s a good thing you weren’t there. They would have killed you.” Dasch later published a memoir laying out his side of the story, but it was mostly ignored.

Hoover made sure the FBI would not pay the price of the American public’s fears. That would be borne by immigrant families caught up in the national security dragnet that swept both coasts. Within a few months after Pearl Harbor, the FBI arrested 264 Italian-Americans, nearly 1,400 German-Americans and over 2,200 Japanese-Americans. Many were never shown evidence leading to their arrest. Beyond those initial arrests, however, came a much heavier cost. Throughout the war, approximately 100,000 Japanese-Americans were forced into internment camps, and 50,000 Italian-Americans were similarly relocated.

For years after the war, Dasch petitioned the U.S. government for a full pardon that would allow him to return, as David Alan Johnson notes in Betrayed, his book about Hoover and the saboteurs. Every time Hoover blocked the request.

While Operation Pastorius may have been the most tangible Nazi threat to unfold on American shores, it was not the last. In January 1945, with Hitler’s regime in its last throes, the U.S. Army uncovered a plan for buzzbomb attacks on the East Coast, providing the New York Times with another bone-shivering headline: “Robot Bomb Attacks Here Held Possible.”